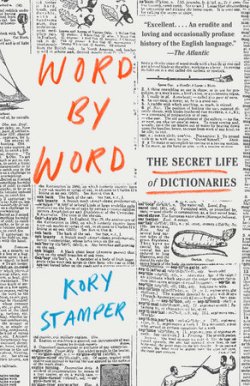

Part memoir, part linguistic escapade, Kory Stamper’s Word by Word: The Secret Life of Dictionaries (2017) is a must-read for anyone who is interested in exploring the stories behind the quirks of the English language.

A lexicographer at Merriam-Webster, Stamper takes readers behind-the-scenes of the editorial process and the history of the dictionary industry. Her style is particularly engaging because she dives deep into the intricacies of the English language, yet expertly keeps her writing light and relatable.

Throughout each chapter, Stamper’s sprachgefühl, or “feeling for language,” is our trusty companion, bounding along with us as she debates the merits of words ranging from “its” to “irregardless.”

She affectionately refers to her sprachgefühl as a both a playful imp and a slippery eel–an inner voice that nudges her in different directions yet remains somewhat out of reach.

Still, she trusts it. It’s the reason she decided to work at Merriam-Webster, and it’s what compels her to always be on the lookout for new words or, more often, new usage patterns of old words. Think “Google” shifting from being a noun to being both a noun and a verb. Or how “like” (which used to mean “body”) gave rise to “likely” and “likewise” and is now a marker of hesitation or, like, a common filler word.

Word by Word is unlike any other book I’ve read on language. It gives readers a behind-the-scenes look at how simple words, like “surfboard” can take an entire working day to define and even simpler words (like “take” or “to”) can take weeks to define.

Editors at Merriam-Webster don’t have office phones. (Too noisy.) So they communicate through email and handwritten notes.

Throughout the book, Stamper also sprinkles witty includes anecdotes about her life as a Merriam-Webster employee. She jokes without restraint about the bland coffee, disorganized filing system, and the contrast between the bubbly sales department and the severely introverted lexicographers.

What I found most fascinating about Word by Word was Stamper’s discussion of how lexicographers at Merriam-Webster scavenge for usage patterns. Tracking word usage–or “reading and marking”–involves underlining words and the context that surrounds them so that you can determine how the words are used and what they mean.

This involves not only pouring over periodicals like Car and Driver, TIme, and Christianity Today, but also snagging language from all corners of life–including cereal boxes, road signs, shampoo bottles, and concert programs–to read and mark for word usage.

Sometimes the lexicographers at Merriam-Webster simply mark words that strike them as relevant; other times, they are tasked with marking every third or fifth word to ensure that no words are glazed over.

“We think of English as a fortress to be defended, but a better analogy is to think of English as a child. We love and nurture it into being, and once it gains gross motor skills, it starts going exactly where we don’t want it to go….We can tell it to clean itself up and act more like Latin; we can throw tantrums and start learning French instead. But we will never really be the boss of it. And that’s why it flourishes.”

–Kory Stamper, Word by Word

This process illustrates that English, like any language, is always in flux. And, often times, the grammatical rules we enforce are arbitrary. They have no foundation in logic but, Stamper writes, were simply “of-the-moment preferences of people who have had the opportunity to get their opinions published and whose opinions end up being reinforced and repeated down the ages as Truth.”

Ever been told that you can’t end a sentence with a preposition? That rule was arbitrarily established by England’s first Poet Laureate, John Dryden.

John Dryden. Seems kind of pompous, doesn’t he?

Dryden worshipped Latin grammar. He would often write a sentence in English, rewrite it in Latin, and then rewrite it again in English. The result was an English sentence that had Latin grammar. And, in Latin, prepositions cannot be placed at the end of a sentence.

The rule has been reinforced over centuries and now, to some, is Unbreakable Law. But as Stamper points out, using the terminal preposition is perfectly acceptable in English and was being used by writers more than five hundred years before Dryden was even born.

The perfect blend of linguistics, history, and wry humor, Stamper’s Word by Word is guaranteed to have you questioning and analyzing their own use of language. And, if you have sprachgefühl, you may just find yourself taking a second look at that cereal box, scribbling down a conversation you overheard on the bus, or maybe even inventing a few words of your own.

Pingback: If You Are Interested in Language, Check This Out | Padre's Ramblings